A Look at New Year Traditions in Japan

New Year in Japan is less about loud countdown parties and more about preparing for a fresh start. The holiday is called お正月 (Oshōgatsu) or 正月 (Shōgatsu), and it’s widely considered the most important celebration of the year. Public offices and many companies—and some schools—close around January 1–3, giving families time to rest, visit relatives, and welcome the new year together, even though convenience stores and many retailers stay open.

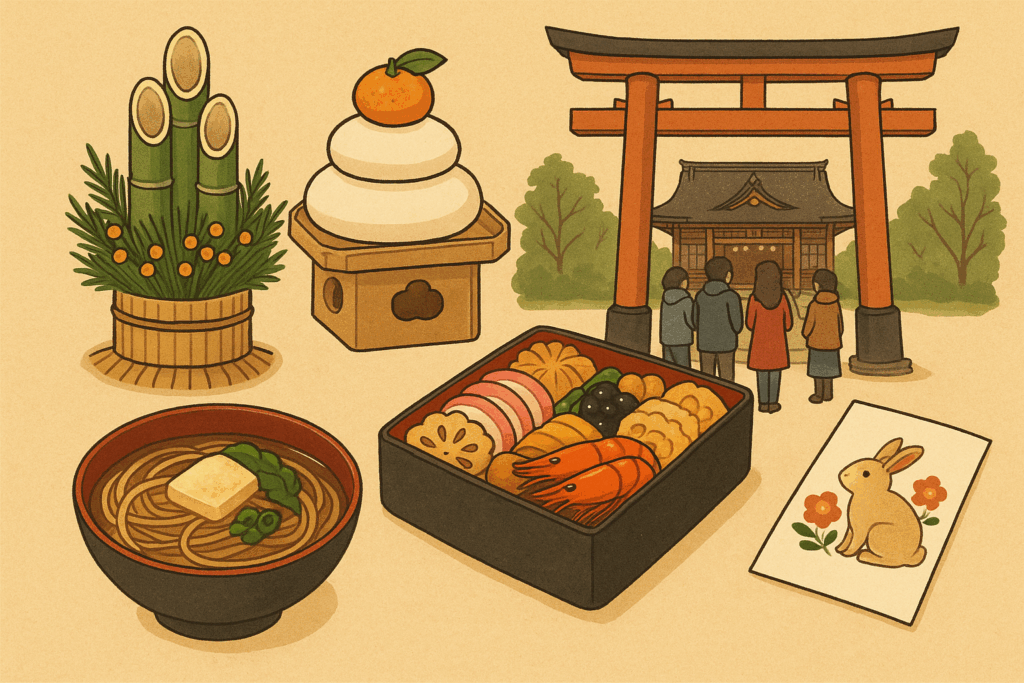

The season begins even before the year turns. In late December many households do 大掃除 (ōsōji), a deep cleaning meant to sweep away the old year’s dust and bad luck. Homes are then decorated with traditional items such as 門松 (kadomatsu)—pine and bamboo arrangements placed at entrances to invite good fortune—and 鏡餅 (kagami mochi), stacked round rice cakes displayed indoors as a New Year offering. These decorations symbolize welcome, strength, and renewal, and you’ll see them in front of houses, shops, and sometimes schools.

Food plays a central role in Oshōgatsu. On New Year’s Eve, families often eat 年越しそば (toshikoshi soba). The long noodles represent longevity and the hope of “crossing over” into the new year smoothly. During the first days of January, people share おせち料理 (osechi ryōri), a set of colorful foods packed into layered boxes. Each dish has a meaning—health, prosperity, fertility, or happiness—and osechi is prepared ahead of time so no one has to cook during the holiday. Another classic dish is お雑煮 (ozōni), a warm soup with mochi rice cakes that varies by region and family tradition.

One of the best-known New Year activities is 初詣 (hatsumōde), the first shrine or temple visit of the year. People go to pray for safety and good luck, buy お守り (omamori) charms, and draw おみくじ (omikuji) fortunes to see what the year might bring. Major shrines can become extremely crowded, especially right after midnight on January 1, and the atmosphere feels both festive and respectful.

One of the best-known New Year activities is 初詣 (hatsumōde), the first shrine or temple visit of the year. People go to pray for safety and good luck, buy お守り (omamori) charms, and draw おみくじ (omikuji) fortunes to see what the year might bring. Major shrines can become extremely crowded, especially right after midnight on January 1, and the atmosphere feels both festive and respectful.

Many families also exchange New Year greetings. A traditional way is sending postcards called 年賀状 (nengajō) so they arrive exactly on January 1. They often include thanks for the past year and wishes for the next, sometimes with the zodiac animal of the year. Even though digital messages are increasing, nengajō remain part of the seasonal atmosphere.

Overall, Japanese New Year feels like a calm reset: cleaning, meaningful food, quiet prayers, and time with family. It’s a reminder to appreciate the year that passed and step into the next one with intention.

あけましておめでとうございます (Akemashite omedetō gozaimasu)! Happy New Year.